In foreign affairs, the great surprise of 2025, has not been tariffs or the geo-politicisation of AI, but the flipping of American foreign policy to apparently align with Russia, jettison the rule of law, tolerate China, and as our recent, prescient note underlined, rediscover Latin America (‘The Land Full of Vibrancy and Hope’). The ‘exit’ of Nicolas Maduro further undermines the rule of law and reinforces the view of a ‘spheres of influence’, where the bad are emboldened and the good are imperiled.

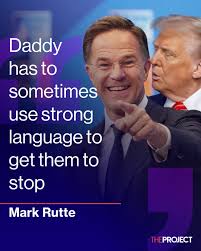

The big disappointment has been the slow, meek reaction of Europe to the above, the low point of which was the reference to Trump as ‘daddy’ by Mark Rutte, former Dutch prime minister and now NATO chief. Indeed, 2025 might also be described as Europe’s ‘neo-con’ year, when its leaders were mugged by the reality of strategic competition, and more specifically the mendacity of Vladimir Putin and the election of Donald Trump.

There are several strands to this. The first is the shock at the delivery of the message that America (the ‘White House’) is in effect dis-engaging from Europe and shattering the idea of the ‘West’. From the shambles of the Munich Security Conference to the communication of the National Security Strategy, there is still a shock felt across the continent to the change of direction that the White House is pursuing. A notable sign of this is how, in the post-Brexit world, Britain has become much closer to Europe on security and defence and is in the lead on strategy around Ukraine. A consequence of America’s ‘flip’ of this reaction, which I feel is not yet appreciated in the US, will be a much reduced willingness to buy American goods and services.

In practical terms, the new geopolitical climate is revolutionising defence spending in Europe. The Baltic and Nordic states, as well as Poland, are all increasing defence budgets amidst warnings of a future confrontation with Russia. Most notably, Germany has cast aside its debt brake to target Eur 1trn in extra defence spending in the next decade, and the EU’s Eur 150bn loan facility has closed its loan round. Europe is now in effect in a three year scramble to build defensive infrastructure, and there is also growing talk of more offensive (i.e. cyber) actions against Russia.

Beyond the manner of the delivery of US diplomacy there is a mixture of anger and confusion in Europe at the stance of the White House. One is the apparent untethered nature of US diplomats like Steve Witkoff, his alleged closeness to Russia and the peace deal proposals he has concocted. This has caused concern because of the time, energy and political capital that European leaders have had to spend (with Ukraine) counteracting the US/Russia proposal.

A second source of ire is the apparent support by the White House for far-right parties in Europe – the AfD, Reform in the UK and the Rassemblement in France – all of whom have proven ties to Russia, all of whom hold 30% or more in opinion polls and all of whom are in direct opposition to governments in the three largest European countries.

It is also worth noting that the tension provoked by the White House has not brought Europe any closer to China – the perceived dumping of Chinese goods (electric vehicles for example) in Europe, and China’s support of Russia’s war in Ukraine are two major sticking points.

One relative bright spot on the horizon is that growth is beginning to pick up across Europe – bank lending is expanding, unemployment already low and lead indicators perking up. In that context it is likely that growth surprises to the upside next year. One great challenge, which has dropped from the policy limelight in the context of the focus on defence, is the Savings and Investment Union (old Capital Markets Union), and this is an essential part of the policy landscape in the coming year.

Looking ahead, across individual countries, there is now a consensus view in the UK that Sir Keir Starmer could be toppled as prime minister by his Labour colleagues (Wes Streeting is favourite to take over, and another Blairite Yvette Cooper, cannot be ruled out either). A recent YouGov poll showed Starmer to be the most unpopular prime minister in the past fifty years, and Rachel Reeves is the most unpopular Chancellor. The only European leader who is further adrift in the opinion polls than Starmer is Emmanuel Macron.

Macron, it seems, has given up, and in France the political debate bypasses him and is steadfastly focused on the next presidential election which should take place in May 2027 though it is not impossible that an attempt is made to unseat him in 2026. The election to watch is in Hungary, where the pro-Russia/anti EU prime minister Viktor Orban is behind in the polls to Peter Magyar’s TISZA party. A return of Hungary to the pro-EU ‘fold’ would be welcome and would constitute a blow to Russia.

To that end, and in the context of the damp squib that was the last EU summit, the litmus test for Europe in 2026 is to stop reacting to the disorder that others sow, but to build a positive narrative around the EU, and critically to riposte in a meaningful way against its adversaries. Greenland might be an early test.

Have a great week (and new year) ahead, Mike