Riddle of the Funds

A friend who lives in an isolated area and therefore in need of good reading material, recently asked me to recommend some geopolitical oriented thrillers. I immediately thought of decent, new writers in the field like David McCloskey and Charles Beaumont, the interesting recent James Stavridis/Eliot Ackerman books that straddle fact and fiction, as well as the scary ‘If Russia Wins’ by Carlo Masala.

However, many of my favourites are from different eras, Laurence Durrell’s ‘White Eagles over Serbia’ set during the Cold War, and then in a bygone period of great power competition, the works of Eric Ambler and of course, Erskine Childers (‘Riddle of the Sands’ ).

The end of globalization and the onset of great power competition means that those works remain relevant though, if on the fourth anniversary of the war on Ukraine European policymakers wanted reading recommendations, I might well propose a book like Sebastian Mallaby’s ‘The Power Law’, or Azeem Azhar’s ‘Exponential’, and to be cheeky, even ‘The Art of the Deal’.

My reasoning, with Europe (the EU, UK, Nordic nations) finally starting to mobilise its factories and innovators to bolster its war economy, is that there remain several missing elements in the quest to build the industrial champions of the European war economy. Europe’s politicians are very good at high minded rhetoric (there are repeated calls to build the European Google, Palantir and Anduril), and even better at racking up debt, but less gifted at spurring large scale innovation.

For instance, the response to the hostile American message to the EU at the 2025 Munich Security Conference was the lifting of the German debt brake, while the recent threat to ‘take’ Greenland has prompted multiple calls for the issue of ‘euro-bonds’.

However, with German military spending and defence related industrial production now taking off, the secret to defence and security innovation lies more in business school texts, than in war college. There are a few elements to highlight here.

The first one touches on a perennial problem for Europe, the lack of depth in financial markets. Amidst an epidemic of defence start-ups and fund launches across Europe, there are still relatively few investment funds focused on the kind of later stage investing required to scale security focused companies to a size where they can become part of the growing industrial infrastructure in Europe. This lacuna owes in part to the failure of Capital Markets Union (now Investment Savings Union), such that few pension funds and institutional managers are investors in ‘strategic autonomy’.

It also reflects a labour market problem – there are simply few investors in Europe who have good knowledge of the defence and dual use ecosystem.

The idea of an ecosystem is the second aspect of the defence investment riddle. A small number of countries have cracked this – the US and France stand out. In the US, like France, the education system provides a rich supply of engineers and technologically capable graduates (e.g. Onera Labs in France), many of whom have a layer of business school training, and in a good number of cases have ties to or experience in the military.

Ecosystems encompass large firms, divisions of the military and defence establishment (i.e. SpaceForce), as well as sector specialist investors. When the elements of such an ecosystem are connected and work together, they can propel an interesting start-up to a viable enterprise in a few years. A developed pan-European ecosystem does not exist, and its cultivation needs to surmount cultural obstacles (as the recent Future Combat Air System (FCAS) debacle has shown), tax and incentive policy, and a more open approach to innovation from large European firms.

Then, the element that is to my observation missing in many new defence focused start-ups and first-time investment funds is the presence of seasoned business operators who have experience in scaling businesses and advising on how best to navigate the various complex government procurement pathways across Europe.

This is a critical omission in the defence sector because government led procurement can help start-ups survive, but not necessarily grow. This is doubly so in dual-use technologies such as cyber security and hardware (including new materials), where ‘go to market’ is a more important imperative than ‘go to war’. Compared to the US, Europe has a short supply of such operators, and in general governments have not done a good job of encouraging them to become part of the ‘strategic autonomy’ economy.

Europe faces a diplomatic disengagement by the US, a grave security threat from Russia and industrial dislocation by China. As such, Europe’s war economy needs to add up to much more than guns and drones, but must rest on innovation, entrepreneurship and ambitious capital.

Have a great week ahead, Mike

Old Money

A recent book, Samuel Moyn’s ‘Gerontocracy in America, highlights the growing concentration of wealth and power in the much older generations in the US, whilst younger generations face historically high valuations in real estate and financial assets, and how this growing intergenerational divide might be mended. Moyn, in my view, has struck a chord that will become one of the new dividing lines in politics, in Asia and the West.

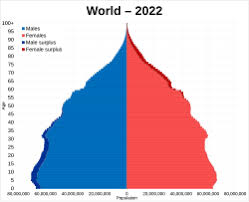

His book brings demographic change into focus, a slow-creeping risk to economies, society and public life, but whose implications are only just surfacing in the public debate. Despite that, from a popular point of view, the sense in many Western countries is that there are too many people, or rather that infrastructure has not kept up pace with population growth – I am writing this in Dublin, which is an excellent case in point.

Yet, the long-run demographic trends – falling fertility, longer life expectancy and a shift in population composition towards a much smaller working (tax paying) population, will have enormous impacts on society, pension systems and debt loads, to name a few economic issues.

As much was evident in Germany’s recent pension reform debate which was nearly upended by Helmut Kohl’s grandson Johannes Volkmann and a group of other young parliamentarians who voiced the right of the younger generation to not have to shoulder the financial burden of their parents’ generation (under the German system, and many others, the working population effectively funds the retirement system of the older generation)..

The best starting point on the outlook for demographics is the United Nations World Population Prospects website. and the data – especially in chart form – are quite striking.

The UN data show that as we approach 2100 the world population will plateau and start to shrink. From roughly 2080 onwards the world population growth rate will turn negative for the first time in centuries (wars apart), as the death rate passes out the birth rate. Within the age cohorts, the over 65 group will expand by a billion people in the next thirty years.

More specifically, at the country level, the US death rate will surpass the birth rate in around 2040, and population growth is likely to only be sustained by immigration. The picture is worse for some European countries – Italy for example is already in negative population growth territory, and the most negative forecast scenario from the UN has the Italian population dropping from over 60 million today to 25 million by 2100 (the same level as when Garibaldi unified the country).

Equally, China, which has been renowned for its economic and population growth, will endure a collapse in the 24–65-year age group, who today number 830 million people and by 2100 are expected to comprise 280 million people. China is projected to be the country most affected by ageing, with its, China’s elderly dependency ratio is projected to surpass 100% by 2080, meaning there will be more people aged over 65 than those aged 15 to 65.

The expected collapse in the working population begs serious questions for the economy – who will pay taxes, sustain pension systems and where will demand for financial assets come from. Markets are not worried, yet.

In general, researchers find that there is a positive link between demographics and asset prices, a finding that is predicated on the rise of the boomer middle class and the coincident equity bull market and fall in bond yields. The idea is that until they retire, working households invest more in real estate, equities and other riskier assets, but then shift to income-oriented assets like bonds as they get older and require income from investments. The oddity in that respect is that despite an ageing population, equities and real estate are very expensive. This may well owe to a growing investment culture, a record level of wealth (USD 500 trillion worldwide) and the prosperity boon that has resulted from globalization.

In this context, old money will become a political target, both in terms of demands for lower inheritance taxes, to more populist measures to tax the ‘old’ and give the ‘young’. For governments who worry about demand for their bonds, wealthier older citizens might make ideal candidates for financial repression (their children would face lower inheritance tax provided that capital spent a period of ‘purgatory’ invested in government bonds – I outlined a similar theme in ‘Patriotic Capital’)

At the same time, pension systems will have to change to accommodate a proportionately smaller number of workers (to pensioners). Private pension systems will become more common, they will invest more, earlier, with a tilt to riskier assets.

Concurrently, I expect to hear more on the need for states to establish sovereign wealth like funds (based potentially on the sale of state assets) to help provide for future pension liabilities. Another concern will be the need for states to cushion the potential blow of AI on workforces (a fund that holds equity in AI firms might be an avenue), at least through a transition period. In the long term, AI and robotics may well allow more older people to work for longer and for more women to enter the workforce. And, I haven’t managed to tackle the topic of later retirement ages and how that will impact the workforce and society.

The effects of demographics are not yet showing up in markets, and are just creeping into the investment industry, but it will become a major fiscal and financial megatrend.

Have a great week ahead, Mike

Boring, boring

The only positive aspect of the grim France versus Ireland rugby match of a week ago was that, serendipitously, I bumped into three brothers from Limerick whom I’ve known for some time. We re-grouped the evening after the match for a pint and a post-mortem, where the chat turned around sports and politics. Drawing the two threads together, one of the brothers noted that in the last ten years the UK has had more ministers for housing (a whopping 14) than Chelsea FC have had managers (12). Readers will immediately grasp the parallels between the two chaotic worlds.

A couple of days later I had a chance to test the hypothesis at Old Trafford during the United vs. Spurs match (readers should not get the impression that I spend my life shuttling from one event to another). United are hardly a paragon of managerial stability, but I hope that in Michael Carrick we have finally rediscovered someone who recognises how the team should play. However, for much of the match, Thomas Frank, the Spurs manager, faced a barrage of abuse from the crowd, and having taken Spurs perilously close to the relegation zone, he was sacked on Wednesday.

The comparison between football and politics, in Britain at least, makes sense in other ways. Both are seeing an infusion of money, ‘overseas’ capital in the case of many British football clubs, and there is a good case to be made that foreign money has found its way into British politics also. Nick Gill, the former Reform UK man in Wales has recently been jailed for bribery (for spreading pro Russia content), and it is the stated objective of the White House team to involve themselves actively on the far-right fringes of British politics.

Both football and politics have in my view, become duller and devoid of what we might call ‘characters’, and both are in thrall to social media, to the irritating end that many MPs seem incapable of giving a speech in parliament without recourse to their mobile phone.

In one way, they are different. There is less violence in football, on and off the field, compared to the 1970’s and 1980’s, though at the same time public life has become much more unpleasant. Sadly, two MP’s have been killed in the past forty years, with both of those in the past ten years, at the hands of political extremists. Many MPs are leaving politics because of the stresses of the position. This pattern is repeated across many other democracies, especially in the case for female politicians.

The ire that is directed towards politicians may be one reason that Sir Keir Starmer is now, according to Ipsos and the FT, the most unpopular prime minister in over fifty years, and his Chancellor Rachel Reeves the most unpopular individual to hold that role. The oddity is that Starmer is honest, steady and importantly has not authored a policy disaster like Brexit. Perhaps, his failing is that like his favourite team Arsenal, he is ‘boring, boring’.

Sir Keir has been prime minister for some eighteen months, which eerily for him, is the average span of the Premiership football manager. Interestingly In this respect there are parallels in the corporate world, where the tenure of CEO’s is shortening to about five years for the large US companies according to work at Harvard and some consulting firms. Like footballers but not MPs, CEO’s are also much better paid.

Since the end of last year, Starmer’s Labour party colleagues have been stalking him, as they might a wounded animal. The deep embroilment of Peter Mandelson in the Epstein scandal has given these colleagues (many of whom know Mandelson very well) the cause to up the pace in the hunt for Starmer’s job, and the resignation of his right-hand man Morgan McSweeney, has only encouraged them. Now, there is ‘blood in the water’ and uncharitably toughts turn to who might replace him, and what the political fall out could be.

A face off between the left leaning Andy Burnham (who does not have a seat in parliament), leftie Angela Rayner and the more centrist Blairite Wes Streeting is likely. An interesting compromise candidate could be energy secretary Ed Miliband, or even foreign secretary Yvette Cooper. My sense is that the British public does not want a more left leaning government, that they are ready for a more EU friendly policy set and that they want the next leader to be decisive.

There is a high chance that Starmer goes, and that in many respects Labour shoots itself in the foot by dismaying the public, and dividing their own party. By weakening themselves they increase the likelihood that a future government could incorporate a coalition of Labour/Liberal Democrats and the Greens. In itself, this would be a new departure (the only coalition since the War was the Tory/Lib Dem one from 2010-2015).

The UK (and the US) are unique in that they have been two party political systems for nearly one hundred years, at least. The structure of electoral systems has much to do with this. In many European countries, it is relatively easy to set up a political party and gain a foothold in parliament. Doing so in the UK has traditionally been very difficult because of the first past the post system.

However, in the post Brexit era, a number of shifts are occurring, that are quickly coming to a head (especially so last week) that will entirely change British politics, and likely mean that after the next election, coalitions could be the norm rather than the exception.

In the past month, Reform has welcomed several high-profile members of the Tory Party. With local elections in May, Nigel Farage has given Tories a deadline of early May to join Reform and a few others may join (Reform won only 5 seats in the last general election, followed by a number of by-elections, it now has 8 MPs). For context, Reform is at 29% in the polls, Conservatives and Labour on 18%, the Liberal Democrats on 13% and the Greens on 14%).

As such, Reform is becoming the (far) right wing party of choice, though it is unlikely they can muster enough decent candidates to win more than 20% of the seats (as opposed to votes).

In order to enter government, Reform would likely have to enter into a coalition with the Tories, but with the recent defections, relations are at a low (Tories slated Braverman on her move).

Then, on the left, the surprise in British politics has been the rise in support for the Liberal Democrats (they have 72 MPs, in stark contrast to Reform), and the sharp rise in support for the Greens. As such, if the distribution of seats in an election followed opinion polls, the next government might well be a left leaning, ‘Green’ coalition, something that would be common in a continental European country but, a complete break with tradition for British politics.

Starmer’s enemies appear committed to getting rid of him but need to take care that the road ahead is untravelled.

Have a great week ahead, Mike

Funny Money

‘It is not speed that kills, it is the sudden stop’

This quote from a paper on currency crises by economist Rudiger Dornbusch came to mind last week as the price of silver having climbed over 100% in a month, collapsed by 30% in an afternoon. The sudden stop in silver is emblematic of many of the problems with financial markets, but also strikes a chord with some of the deeper changes materialising within the world economy, such as the rising quantum of debt, and recent attacks on Jerome Powell.

As we noted in ‘Grasshopper’, silver used to be a money, though the propensity of some users to mix it with inferior metal lead Sir Thomas Gresham to coin Gresham’s law that ‘bad money drives out the good’. In bulk form, silver and more so gold, was good enough to be a money, and to back up the paper money system until 1971 when the gold standard came to an end (one could present dollars to a bank and demand gold in return).

Without the backing of gold, the reasons people held and used paper (fiat money) were determined largely by important intangible factors – such as the rule of law, policy credibility, quality of institutions, as well as the economic usage of that paper – did central banks hold it as a reserve currency, is it widely traded and are financial institutions happy to use it? On most of these criteria, investors, businesses and central banks avoid China’s renminbi, but for the same reasons have been very happy to use the dollar, and to a lesser extent the euro. But, that might be changing.

First of all, as globalization crumbles, there is a rise in distrust, notably in the dollar. There are two facets to this.

In my notes, I have mentioned the work of Barry Eichengreen a number of times. He is the academic authority on currencies and in a paper entitled “Mars or Mercury? The Geopolitics of International Currency Choice” written with two economists at the ECB, he finds that military and geopolitical alliances are a significant factor in explaining currency strength. The rationale is that a country that is geopolitically well placed is engaged with and trusted by its allies through trade and finance.

Unsurprisingly one of the main implications of the “Mars or Mercury?” paper is that in a scenario where the United States withdraws from the world and becomes more isolationist, its strategic allies no longer become enthusiastic buyers of US financial assets and long-term interest rates in the United States could rise by up to 1 percent (there would be fewer buyers of American government debt), according to the paper. As such the many geopolitical events at the start of the year may now have triggered a move away from US assets.

A related move is that the institutions behind the dollar are also under attack, and from outside at least, look less sure. The mid-term elections and the way in which they are held, will be instructive.

The nomination of Kevin Warsh as the next head of the Federal Reserve is another important development. My instinct, unlike other economists is to put less store on his family background, and suspicions that he might not be independent, simply because any political bias or even more general lack of judgement, will be quickly punished by markets. I agree with stances he has taken in recent years, notably against the ongoing deployment of quantitative easing. The really interesting element of the Warsh Fed will be the partnership he forms with Scott Bessent, and I suspect that this ‘accord’ will focus on creating the means by which the financial sector (notably banks) becomes the driving engine of the economy.

There are other factors at work. China has been aggressively courting its emerging market trading partners to use the renminbi, and this is beginning to show up in currency flows (the renminbi has jumped from 2% to 4% of international trade driven transactions in the last two years, according to a research paper from the Fed). The big shift however is central banks, who for a variety of reasons, mostly geopolitical, have a newfound penchant to hold gold as a reserve, rather than Treasuries.

In this regard, buying by central banks has been the new development in the gold market in recent years, this has been surpassed by the side-effects of the financialisaton of gold and silver. To state it simply, the existence of exchange traded funds (with liquid options markets on these ETFs) has allowed retail investors, and institutions, to speculate on the price of gold. In the old days one had to buy it in barloads, and in Zurich at least, take the No. 13 tram to visit the gold, as we described in a note, Marmite .

The lashings of financial products that have been built around gold and silver have to a large extent transformed them from stores of value, into Frankenstein like speculative assets. The 30% collapse in the price of silver last week had many causes, but most of them can be traced to financial engineering. As such, this is a warning that, in a world with more US PE funds than McDonalds in the US and with more ETF’s than stocks, financialisaton can ultimately be highly damaging.

Another angle on this is bitcoin, a techno-financial response to the growing lack of trust in economies. Some commentators have described it as digital gold, but it looks to have failed the test of being a money and is most certainty not a safe asset. I regard it as a risk asset, in a small, narrow pantheon with art, penny stocks and racehorses. Indeed, its utility as an instrument to transfer money is also diminishing, in a world where stablecoins are more prevalent, and where fintech is getting better (and cheaper) at facilitating transactions. It might be next for a stress test.

Have a great week ahead, Mike

Constellations

One of the highly unique, and fascinating characteristics of this era of unravelling is the way we increasingly look at the world from a geopolitical rather than a geographic point of view. In previous phases in history, geography and geopolitics aligned neatly – for example the democratic West faced off against the communist East while economically, the North was well ahead of the South. Now, select countries from disparate parts of the world share the same dilemmas and challenges. Japan, as a middle power, arguably has more in common geopolitically with the UK, than it does with Indonesia. In turn, Singapore and Ireland, arguably share the same geopolitical stress points.

In the post globalized world, new coalitions and constellations of countries are beginning to emerge. That much was on display at Davos two weeks ago, when Canadian prime minister Mark Carney eloquently pleaded the case of the democratic ‘middle powers’ and the need for them to collaborate. His speech was followed by the far less eloquent launch of Donald Trump’s ‘Board of Peace’, which is a ragtag band of largely developing countries not known for their commitment to the rule of law and appreciation of human rights.

As the various threads of globalization – from the use of the SWIFT payment system to energy pipelines like Nord Stream, the ‘special relationship’ between the UK and the US, NATO, USAID, and many more, fall by the wayside, new groups and alignments emerge, and in the rest of this note I will sketch some of them.

To start at the top of the pyramid, regular readers will know that David Skilling and I have extensively researched the phenomenon of small, advanced economies – a group that spans Sweden, Singapore, New Zealand, the Netherlands, Ireland, Belgium, Norway, Finland, Switzerland, Austria and Denmark, and that may in future incorporate the Gulf States.

Culturally, these countries are very different but share the same economic and social successes (‘happiest place to live’, ‘best rule of law’, ‘highest GDP’), and a common policy recipe that is based on innovation, openness, education and social cohesion. While we have even tried to create a policy forum for these countries (the ‘g20’), they do not act as a formal block, but actively compare notes behind the scenes. For example, the Nordic states are learning from each other and collaborating on immigration, while Ireland urgently needs to follow the examples of Singapore and Norway on defence.

Then, below the small, advanced economies are the ‘middle powers’, sizeable, developed countries, many of whom enjoyed periods of international dominance, but are now beset by demographic issues (ageing and immigration), and are searching for a defined geopolitical role. Japan, the UK, Canada, Korea, Australia and Russia (not big enough economically to be a superpower, and not nice enough either). With the exception of Russia, the middle powers are democracies and most are eager that the world stays much the same as it was during the period of globalization (at least in the case of Keir Starmer). As such they are beginning to hedge bets by aligning with larger powers, Russia with China, and the UK is now cultivating much better relations with the EU.

Looming over the middle powers are the three ‘great powers’ – China, the US and the EU, each with their strengths – military, finance and technology for the US, culture, liberal democracy, well-being and cities in the case of Europe, and industry and cultural cohesion in the case of China.

They will be the pillars of the emerging multipolar world, and in contrast to the globalized era where most countries adopted the American way of doing things, these three ‘blocs’ will increasingly do things their own, culturally specific way. AI is an example, but corporate governance might be another tack. In addition to these three behemoths, a ‘Fourth Pole’ made up of a core of India and the Gulf states, is possible, as we wrote back in November.

Those classifications still leave about fifty percent of the world’s population unaccounted for, whose nations collectively labour under the term ‘Global South’. These countries, from Nigeria to Indonesia to Bangladesh, share similar policy problems – the building of e-commerce driven economies, healthcare and urbanisation, to name a few but they are not at all at the level of policy exchange as the small, advanced economies, and many of them do not have structured economic models.

For some, the idea of the ‘Fourth Pole’ can become an interesting organizing point, but to a very large extent the survival of existing world institutions, from the UN to the World Bank, now depends on the large, populous emerging economies. Equally, the directions that these countries take in their political economy – do they follow the ‘Chinese model’, the European democratic one, or something else altogether. This policy question is vastly underestimated in the discourse on international economics and politics, partly because the ‘great powers’ are not leading by example.

Have a great week ahead, Mike

Arktika

In 2007 two Russian mini-subs, Mir-1 and Mir-2, dived over 4,000 metres below the Arctic Circle to plant a titanium Russian flag, and so launched a primitive claim to the geological treasures at the top of the world. In highly Bond-esque fashion, the subs were supported by Mi-8 helicopters and the Rossiya, Russia’s most powerful nuclear-powered icebreaker.

The exploit was criticized by the then Canadian foreign minister as ‘15th century’ buccaneering but won the three Russian expedition leaders the medal of ‘Hero of the Russian Federation’ (they were accompanied by a Swedish scientist and an Australian adventurer).

The episode highlighted how the scramble for rare places (we wrote about this in 2021) – the Arctic, Antarctic and outer space, are becoming strategic theatres in a world of great power rivalry. As much was emphasized in 2011 when then Secretary for State Hilary Clinton attended the Arctic Council meeting in Nuuk, a hitherto obscure club, to strengthen America’s commitment to the Arctic.

In that context, it is no surprise that the Trump administration has discovered the strategic importance of Greenland, although there is not a single mention of it in the recent National Security Strategy document. The White House might have asked nicely and had its way to place listening stations and missile batteries in Greenland, but instead the President has banalised his office and his country, and placed in jeopardy the most important geopolitical alliance of the past twenty years.

In doing so he has proven my ‘Rule of Unravelling’ which states that in the post globalization era, all of the constructive institutions and values of the globalized world will be stress-tested, in some cases to breaking point. For instance, the UN is invisible and impotent, and the most sacred of American institutions, the Federal Reserve, has come under a full-frontal attack in recent months. NATO it seems is next.

In most European capitals, especially those with large professional armies, there is considerable doubt that, under the Trump administration, the US will be a reliable ally. The immediate implication is to change the calculus that underpins any security guarantee for Ukraine, and indeed the process by which Ukraine will eventually become a member of the European Union.

Europe already significantly outstrips the US in terms of the extent to which it funds Ukraine (relative to GDP, Denmark is the biggest donor), but the intent of this aid will now have to become more lethal, in terms of what Ukraine can do with the arms provided to it, and craftier, in terms of the ways Ukraine can work with European armies to upset Russia’s war machine.

More broadly, there is also growing chatter that NATO is defunct, and will in effect be replaced by a European army (the Spanish foreign minister, amongst others, called for this last week).

A first step here might be an augmentation (and accelerated implementation) of the EU SAFE (Security Action for Europe) program that allows member states to borrow to fund military equipment for joint use, especially where the bulk of that equipment is made in the EU. Canada is a member of the SAFE, and stupidly the EC made it all but impossible for the UK to join. But, US arms manufacturers will have a hard time selling in Europe.

An EU army could very easily be put together around the structures of existing cooperation agreements, and of course, the structures that have been put in place by NATO. Yet, there is still a considerable amount of work to do however on optimizing collaboration in areas like cyber warfare, intelligence sharing and logistics infrastructure (the EU aims to create a ‘Military Schengen’ by 2027).

The aim of such an army would be the defence of European interests and territories, which in practice takes aim at Russia, but can be broadly interpreted to also cover counter-terrorism, space and the deep seas. In the context of the spat over Greenland, the composition of such an army could encompass elements that are not traditionally classed as military activities, such as economic war, but that in a total war world, might be part of the greater arsenal.

In Europe, the response to each crisis is to create a ‘Union’. In the same way that the euro-zone crisis led to the idea of Capital Markets Union, Europe’s ‘neo-con’ moment may produce a ‘Defence Union’, but unlike CMU, there is now a deadly sense of urgency. To my mind, it is still not at all clear that Europe’s political leaders are ready to command a large, capable military machine.

In a recent note ‘Year of the Riposte’ and in a talk at University College Cork with Prof. Andrew Cottey (‘Europe under Siege), I highlighted the litany of challenges that have been put to European leaders by the White House, China and Russia. In every case, the response has been a mixture of panic and a floundering search for compromise. Europe still dances to the tune set by Trump and others, as the Greenland fiasco has shown.

For example, in an underestimated speech at Davos, Friedrich Merz told the audience that ‘he gets it’ on defence and security. Yet, military procurement and recruitment are inefficient and sluggish.

Europe’s leaders have not yet passed the test set out in our recent ‘Riposte’ note ‘the litmus test for Europe in 2026 is to stop reacting to the disorder that others sow, but to build a positive narrative around the EU, and critically to riposte in a meaningful way against its adversaries’.

Soon they will have no choice, In 2019, Emmanuel Macron boldly stated that ‘NATO is brain dead’. It is now.

Have a great year ahead, Mike

Persepolis

In October 1971, a time when Mao ruled China, Brezhnev was in charge in the USSR and Nixon president of the USA, Maxim’s, the famous Parisian restaurant closed for two weeks so that staff could prepare the restaurant’s greatest order – the feast organised by the Shah of Iran to celebrate the 2500th anniversary of the establishment of the Persian empire by Cyrus the Great.

The Shah’s celebration became known as the greatest party of all time (Life magazine called it ‘the party of the century’) and became highly controversial for its lavishness. For instance, nearly 300 red Mercedes were used to ferry guests around a large, tented city and in the end Maxim’s and other establishments sent some eighteen tonnes of food to Iran. Waiters had to open and taste all of the bottles of Chateau Lafite Rothschild 1945 for poison. Many of the world’s royal families attended, as did a range of social and political figures from Grace Kelly to Tito to Haile Selassie, to Imelda Marcos. It’s perhaps no surprise that this display of excess was followed a few years later by the Iranian Revolution.

The spectacle of the Shah’s party, his ties to foreign governments and the cruelty of his secret police and a drawn-out recession contributed to months of protests in the late 1970’s, which then led to the Revolution. One of the best accounts of the Revolution is a somewhat accidental one – Desmond Harney’s excellent eyewitness account of the revolution “The Priest and the King.” At the time, Harney worked in Tehran. He had been ready to leave Iran on vacation, but for work-related reasons he remained, and then witnessed the eruption of the revolution around him.

My other Revolution-related thought is of former Ayatollah Khomeini, who, on disembarking the Air France aircraft that took him back to Tehran on the outbreak of the revolution, was asked by ABC anchorman Peter Jennings how he felt about his return to Iran. “Nothing. I feel nothing,” was the alleged response. It gave a pointer as to the austere image Mr. Khomeini wanted to portray and of his cold single-mindedness. The fact that the man who translated Khomeini’s comments, was executed three years later, was another clue as to what would follow.

The regime that Khomeini created has outlasted many others – perhaps only the late Fidel Castro and especially so the late Queen Elizabeth II of England have seen as many US presidents, German chancellors, among others, pass on and off the world stage. While Iran has until recently been a dominant player in the Middle East from a geostrategic point of view, it has, to be polite, not been an economic success.

Thus, in keeping with the template of revolutions, high prices, scarcity of food and fuel, and a broken economy, are triggering protests across Iran, that have become so vast, that expectations are growing that Iranians may eject their leadership. That moment may not be too far off, but the path to an Iran that benefits its people remains a difficult one.

Not only are its geriatric rulers stubbornly cut off from its people and the outside world, they have historically, to a worrying extent (this was especially the case under former prime minister Mahmoud Ahmadinejad), relied on heightened tension with the US, Israel and other ‘enemies’ for political oxygen. Also, economically, Iran is like Russia in that most of the assets and resources in the economy are held by a small number of people (IRG, business owners, clerics) who form a sclerotic elite around the theocrats. Breaking their hold on the economy will be difficult, even under a new regime.

Neither is regime change obvious. The name of the Shah’s son Reza Pahlavi is circulating widely (in the West) as a possible figurehead, but the story of the ‘greatest party’ and the memories of his brutality are at least two reasons why he will not lead a ‘new’ Iran. At the same time, it is not obvious what individuals or groups might replace the regime, if it came to that.

A further complication is that Iranians are highly distrustful of interventions from abroad, indeed some people joke that Iran is the only country in the world where MI6 is still considered to be a force to be reckoned with. Military intervention by the US or other states may not be welcome.

The EU is slightly less distrusted than the US and the UK, and it should take a more active stance – in terms of further sanctions, asylum for the hundreds of young people who have been jailed, organise the supply of communication technology into Iran (VPN’s, satellite technology), and potentially begin to plan to assist and shape a transition process.

Iran has been weakened economically by sanctions, humiliated by Israel and had its military capability enfeebled but sadly, the state still has an array of resources with which to repress its people.

My sense is that the brutal repression in Iran will continue now (with very little visible public support in the US and Europe), and the economy will weaken further. An opening may come when the Supreme Leader, Khamenei dies – he is 86 and suffers from cancer. This event could provide the cover for a discrete but meaningful shift in policy, and the start of negotiations on sanctions and Iran’s nuclear program, and the beginning of a more promising era.

Have a great weekend ahead, Mike

Praefectus

Benjamin Jowett is one of the prominent figures in the long history of Balliol College. Jowett, a scholar of Plato and university reformer, was Master of Balliol from 1870 to 1893, where one of his preoccupations was the production of upstanding young men who would then populate the civil service, and in particular who would be sent to ‘run’ India (Jowett favoured a thorough grounding in Greek and Latin as preparation for this task).

It is an understatement to say that India suffered under British rule, during the colonial era (roughly 1700 to 1947) which was marked by the activities of the East India Company, India’s share of world GDP fell from 26% to 4% (after the Second World War). It is still recovering today.

To draw the obvious comparison with Venezuela, which is apparently now to be run from Washington in imperial style (will Marco Rubio be referred to as the Praefectus of Venezuela?), it at least does not have to worry about having its economy destroyed, the revolutionary socialist governments of the past twenty-five years have done a good job of that. Rubio is not made in the mould of Jowett’s scholars, but he speaks Spanish, which will be useful. A knowledge of finance will also be handy, to tackle the mountain of debt that Venezuela owes.

In a week where the American president has been scurrying around like a giddy child opening Pandora’s boxes, the strategy for Venezuela is not yet clear, and it could go very badly wrong, especially if the factions within the current Venezuelan regime start to disagree violently.

The apparent upside is Venezuela’s oil reserves and refining capacity, but this will take a long time and much capital to realise. Indeed, the process of extracting and monetising oil, and driving this wealth into an economy is something that few economies have mastered.

In this regard, the idea of ‘Dutch disease’, a concept that initially referred to the effect of large gas finds on the Dutch economy, is well known, and colloquially, it describes the way the presence of natural resources can (negatively) skew the economic development of a country. Angola, which has been described as a ‘successful failed state’ for the way it has managed to extract and process oil, but does little else, is an example. Nigeria, Russia and of course Venezuela are other examples.

To their credit, the Gulf economies are good examples of states that have used the wealth generated by natural resources in a very ambitious way, whilst top of the league table are Canada, and Norway. Norway’s sovereign wealth fund is the benchmark for many others, and it bears imagining what the UK could have achieved by channelling the wealth from North Sea oil and gas reserves into a sovereign wealth fund from the 1980’s onwards.

If there is a distinguishing factor across the relative success of the above nations it is the rule of law (and its associated values – policy clarity, strong institutions, and enlightened decision makers). The concept of the rule of law (I can recommend a book of that title by Tom Bingham, formerly Lord Chief Justice and Master of the Rolls and like Jowett a Balliol alumni) should be clear to most readers, but its benefits are even more apparent when it is taken away. In this regard, a comment from a US oil company executive regarding investment in Venezuela (in the FT) to the effect that “No one wants to go in there when a random f…g tweet can change the entire foreign policy of the country’ is illustrative of the benefits of the rule of law. Similarly, threats by President Trump to curb the dividend policy of defence companies, and institutional ownership of housing also contribute to policy uncertainty.

World institutions like the IMF and World Bank have produced tons of research demonstrating the link between the rule of law and growth, and stability. Yet the world that ushered in these institutions and globalization, is crumbling, vandalised by ‘world kings’ (Boris Johnson’s phrase) who act in an arbitrary way. Germany’s President Frank-Walter Steinmeier made an important speech to this effect last week.

The litmus test of this view will be the flow of capital. For the moment, the market view seems to be that ‘world kings’ get things done, and markets are reacting in kind. However, there are looming risks, notably the diverging values between the White House and Europe.

If world leaders were stupefied by the raid on Caracas, there was near hysteria in Europe at the suggestion by President Trump and his advisers that the US would annex Greenland. Though the initial reaction from politicians and commentators across Europe was perhaps overblown, there is a gulf between the American view of the White House’s foreign policy, and that of allies, and in the medium to long term this growing lack of alignment and trust will prove damaging.

Have a great week ahead, Mike

2026 – Year of the Riposte

In foreign affairs, the great surprise of 2025, has not been tariffs or the geo-politicisation of AI, but the flipping of American foreign policy to apparently align with Russia, jettison the rule of law, tolerate China, and as our recent, prescient note underlined, rediscover Latin America (‘The Land Full of Vibrancy and Hope’). The ‘exit’ of Nicolas Maduro further undermines the rule of law and reinforces the view of a ‘spheres of influence’, where the bad are emboldened and the good are imperiled.

The big disappointment has been the slow, meek reaction of Europe to the above, the low point of which was the reference to Trump as ‘daddy’ by Mark Rutte, former Dutch prime minister and now NATO chief. Indeed, 2025 might also be described as Europe’s ‘neo-con’ year, when its leaders were mugged by the reality of strategic competition, and more specifically the mendacity of Vladimir Putin and the election of Donald Trump.

There are several strands to this. The first is the shock at the delivery of the message that America (the ‘White House’) is in effect dis-engaging from Europe and shattering the idea of the ‘West’. From the shambles of the Munich Security Conference to the communication of the National Security Strategy, there is still a shock felt across the continent to the change of direction that the White House is pursuing. A notable sign of this is how, in the post-Brexit world, Britain has become much closer to Europe on security and defence and is in the lead on strategy around Ukraine. A consequence of America’s ‘flip’ of this reaction, which I feel is not yet appreciated in the US, will be a much reduced willingness to buy American goods and services.

In practical terms, the new geopolitical climate is revolutionising defence spending in Europe. The Baltic and Nordic states, as well as Poland, are all increasing defence budgets amidst warnings of a future confrontation with Russia. Most notably, Germany has cast aside its debt brake to target Eur 1trn in extra defence spending in the next decade, and the EU’s Eur 150bn loan facility has closed its loan round. Europe is now in effect in a three year scramble to build defensive infrastructure, and there is also growing talk of more offensive (i.e. cyber) actions against Russia.

Beyond the manner of the delivery of US diplomacy there is a mixture of anger and confusion in Europe at the stance of the White House. One is the apparent untethered nature of US diplomats like Steve Witkoff, his alleged closeness to Russia and the peace deal proposals he has concocted. This has caused concern because of the time, energy and political capital that European leaders have had to spend (with Ukraine) counteracting the US/Russia proposal.

A second source of ire is the apparent support by the White House for far-right parties in Europe – the AfD, Reform in the UK and the Rassemblement in France – all of whom have proven ties to Russia, all of whom hold 30% or more in opinion polls and all of whom are in direct opposition to governments in the three largest European countries.

It is also worth noting that the tension provoked by the White House has not brought Europe any closer to China – the perceived dumping of Chinese goods (electric vehicles for example) in Europe, and China’s support of Russia’s war in Ukraine are two major sticking points.

One relative bright spot on the horizon is that growth is beginning to pick up across Europe – bank lending is expanding, unemployment already low and lead indicators perking up. In that context it is likely that growth surprises to the upside next year. One great challenge, which has dropped from the policy limelight in the context of the focus on defence, is the Savings and Investment Union (old Capital Markets Union), and this is an essential part of the policy landscape in the coming year.

Looking ahead, across individual countries, there is now a consensus view in the UK that Sir Keir Starmer could be toppled as prime minister by his Labour colleagues (Wes Streeting is favourite to take over, and another Blairite Yvette Cooper, cannot be ruled out either). A recent YouGov poll showed Starmer to be the most unpopular prime minister in the past fifty years, and Rachel Reeves is the most unpopular Chancellor. The only European leader who is further adrift in the opinion polls than Starmer is Emmanuel Macron.

Macron, it seems, has given up, and in France the political debate bypasses him and is steadfastly focused on the next presidential election which should take place in May 2027 though it is not impossible that an attempt is made to unseat him in 2026. The election to watch is in Hungary, where the pro-Russia/anti EU prime minister Viktor Orban is behind in the polls to Peter Magyar’s TISZA party. A return of Hungary to the pro-EU ‘fold’ would be welcome and would constitute a blow to Russia.

To that end, and in the context of the damp squib that was the last EU summit, the litmus test for Europe in 2026 is to stop reacting to the disorder that others sow, but to build a positive narrative around the EU, and critically to riposte in a meaningful way against its adversaries. Greenland might be an early test.

Have a great week (and new year) ahead, Mike

A Land Full of Vibrancy and Hope

Avid readers of the ‘Levelling’ book will know that some years ago, I wrote

Latin America remains part of the satellite region of the US pole. Sadly, it has been overlooked by Washington. The prime example of this neglect is Venezuela. The country is failing and in the grip of an underreported humanitarian crisis. Economically, this crisis may lead China to take a deeper role in Venezuela and in its oil production. Diplomatically, the lack of a comprehensive reaction from Washington brings to mind an article entitled “The Forgotten Relationship” that Jorge Castaneda published some years ago in Foreign Affairs in which he bemoaned the deteriorating relationship between Latin America and the United States.

Finally, my pleas are heard, and the White House is organizing a rescue (by gunboat) of Venezuela, and possibly much of Latin America.

While it is hard to know how the new engagement between the Trump administration and the fifth largest repository of oil reserves is going to play out, this administration is different to many of its predecessors in taking an active interest in Latin America – note the partisanship with regard to Brazil, generally good relations with Mexico, a chumminess with Milei and the likely support for the new president of Chile.

Despite very active backchannelling between the US military and the Venezuelan army the course that events might take is unclear, and laden with risks – the chaos of popular unrest in Venezuela, the risks that criminals in Venezuela and surrounding countries become involved (and strike in the US), or indeed the risk that other actors or countries use any regime change in Caracas to hurt the US, cannot be ruled out. Another risk is that some of Venezuela’s allies – Iran, China and Russia – become obstreperous, and dig in with Maduro and his cohorts, or that they use any change of government in Caracas to further their own ends. It is worth noting that only last week China launched a policy document entitled ‘Latin America and the Caribbean: A Land Full of Vibrancy and Hope’.

This is a significant risk of the Trump administration’s fetish for a spheres of influence motivated foreign policy. In the recent school boyish ‘National Security Strategy’, which has caused great anguish in the diplomatic parlors of Europe, the document refers to the ‘Trump Corollary’ to the Monroe Doctrine.

For context, the Monroe Doctrine was likely the first coherent, muscular expression of American foreign policy – at the time it was aimed at keeping the Spanish and other pesky European powers out of Central and Southern America. Indeed, the dithering by the large European powers (notably France) over the long running Mercosur trade agreement, suggests that the European dare not go back to Latin America.

The NSS document gives a good deal of attention to Latin America, and this tilt will have the active support of Secretary of State Marco Rubio. Like it or not, Latin America is now in Washington’s sphere.

However, more generally, the establishment of a spheres of influence mindset in international relations may give the likes of Russia and China the sense that they may do as they wish in their own spheres of influence. In the same way that the invasion of Iraq, on the basis of flimsy evidence of weapons of mass destruction, apparently led Vladimir Putin to believe that the West was no longer respecting the rules of the international order, the ‘Trump Corollary’ strategy is a green light for bad policy actors.

That would of course be bad news for Taiwan, and perhaps Vietnam, the Philippines and Japan, who all to some extent count on the notion of a US security guarantee for Taiwan. It may also prove confusing for the US military which, when not loitering off the coasts of Cuba and Venezuela, is organized around the concept of a grand battle in the South China Sea.

Beyond the obvious implications for Ukraine, there are plenty of other open questions – will China take the ‘Stans’ from Russia, and who gets Africa? Russian mercenaries have forced France out of at least seven countries and China has a hand in nearly every African economy. The cancellation of US AID is already having deadly consequences for human and animal life.

A world of spheres of influence might conjure the diplomacy of the Great Game, but it would leave many countries worse off, and the nondemocracies of the world free to abuse their military and economic power.

A forlorn reminder of this was the jailing of Jimmy Lai, the Hong Kong democracy activist last week. Few Western governments were audible in protesting this act, save Britain, which used to count Hong Kong as part of its sphere of influence (Lai has British citizenship). The silent snuffling out of democracy in Hong Kong is the act that brought the curtain down on globalization in my view. An American spheres of influence foreign policy will sow further chaos.

Have a great Christmas week ahead, Mike (there won’t be a note next week, we return on the 4th January)