The only positive aspect of the grim France versus Ireland rugby match of a week ago was that, serendipitously, I bumped into three brothers from Limerick whom I’ve known for some time. We re-grouped the evening after the match for a pint and a post-mortem, where the chat turned around sports and politics. Drawing the two threads together, one of the brothers noted that in the last ten years the UK has had more ministers for housing (a whopping 14) than Chelsea FC have had managers (12). Readers will immediately grasp the parallels between the two chaotic worlds.

A couple of days later I had a chance to test the hypothesis at Old Trafford during the United vs. Spurs match (readers should not get the impression that I spend my life shuttling from one event to another). United are hardly a paragon of managerial stability, but I hope that in Michael Carrick we have finally rediscovered someone who recognises how the team should play. However, for much of the match, Thomas Frank, the Spurs manager, faced a barrage of abuse from the crowd, and having taken Spurs perilously close to the relegation zone, he was sacked on Wednesday.

The comparison between football and politics, in Britain at least, makes sense in other ways. Both are seeing an infusion of money, ‘overseas’ capital in the case of many British football clubs, and there is a good case to be made that foreign money has found its way into British politics also. Nick Gill, the former Reform UK man in Wales has recently been jailed for bribery (for spreading pro Russia content), and it is the stated objective of the White House team to involve themselves actively on the far-right fringes of British politics.

Both football and politics have in my view, become duller and devoid of what we might call ‘characters’, and both are in thrall to social media, to the irritating end that many MPs seem incapable of giving a speech in parliament without recourse to their mobile phone.

In one way, they are different. There is less violence in football, on and off the field, compared to the 1970’s and 1980’s, though at the same time public life has become much more unpleasant. Sadly, two MP’s have been killed in the past forty years, with both of those in the past ten years, at the hands of political extremists. Many MPs are leaving politics because of the stresses of the position. This pattern is repeated across many other democracies, especially in the case for female politicians.

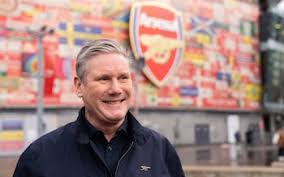

The ire that is directed towards politicians may be one reason that Sir Keir Starmer is now, according to Ipsos and the FT, the most unpopular prime minister in over fifty years, and his Chancellor Rachel Reeves the most unpopular individual to hold that role. The oddity is that Starmer is honest, steady and importantly has not authored a policy disaster like Brexit. Perhaps, his failing is that like his favourite team Arsenal, he is ‘boring, boring’.

Sir Keir has been prime minister for some eighteen months, which eerily for him, is the average span of the Premiership football manager. Interestingly In this respect there are parallels in the corporate world, where the tenure of CEO’s is shortening to about five years for the large US companies according to work at Harvard and some consulting firms. Like footballers but not MPs, CEO’s are also much better paid.

Since the end of last year, Starmer’s Labour party colleagues have been stalking him, as they might a wounded animal. The deep embroilment of Peter Mandelson in the Epstein scandal has given these colleagues (many of whom know Mandelson very well) the cause to up the pace in the hunt for Starmer’s job, and the resignation of his right-hand man Morgan McSweeney, has only encouraged them. Now, there is ‘blood in the water’ and uncharitably toughts turn to who might replace him, and what the political fall out could be.

A face off between the left leaning Andy Burnham (who does not have a seat in parliament), leftie Angela Rayner and the more centrist Blairite Wes Streeting is likely. An interesting compromise candidate could be energy secretary Ed Miliband, or even foreign secretary Yvette Cooper. My sense is that the British public does not want a more left leaning government, that they are ready for a more EU friendly policy set and that they want the next leader to be decisive.

There is a high chance that Starmer goes, and that in many respects Labour shoots itself in the foot by dismaying the public, and dividing their own party. By weakening themselves they increase the likelihood that a future government could incorporate a coalition of Labour/Liberal Democrats and the Greens. In itself, this would be a new departure (the only coalition since the War was the Tory/Lib Dem one from 2010-2015).

The UK (and the US) are unique in that they have been two party political systems for nearly one hundred years, at least. The structure of electoral systems has much to do with this. In many European countries, it is relatively easy to set up a political party and gain a foothold in parliament. Doing so in the UK has traditionally been very difficult because of the first past the post system.

However, in the post Brexit era, a number of shifts are occurring, that are quickly coming to a head (especially so last week) that will entirely change British politics, and likely mean that after the next election, coalitions could be the norm rather than the exception.

In the past month, Reform has welcomed several high-profile members of the Tory Party. With local elections in May, Nigel Farage has given Tories a deadline of early May to join Reform and a few others may join (Reform won only 5 seats in the last general election, followed by a number of by-elections, it now has 8 MPs). For context, Reform is at 29% in the polls, Conservatives and Labour on 18%, the Liberal Democrats on 13% and the Greens on 14%).

As such, Reform is becoming the (far) right wing party of choice, though it is unlikely they can muster enough decent candidates to win more than 20% of the seats (as opposed to votes).

In order to enter government, Reform would likely have to enter into a coalition with the Tories, but with the recent defections, relations are at a low (Tories slated Braverman on her move).

Then, on the left, the surprise in British politics has been the rise in support for the Liberal Democrats (they have 72 MPs, in stark contrast to Reform), and the sharp rise in support for the Greens. As such, if the distribution of seats in an election followed opinion polls, the next government might well be a left leaning, ‘Green’ coalition, something that would be common in a continental European country but, a complete break with tradition for British politics.

Starmer’s enemies appear committed to getting rid of him but need to take care that the road ahead is untravelled.

Have a great week ahead, Mike