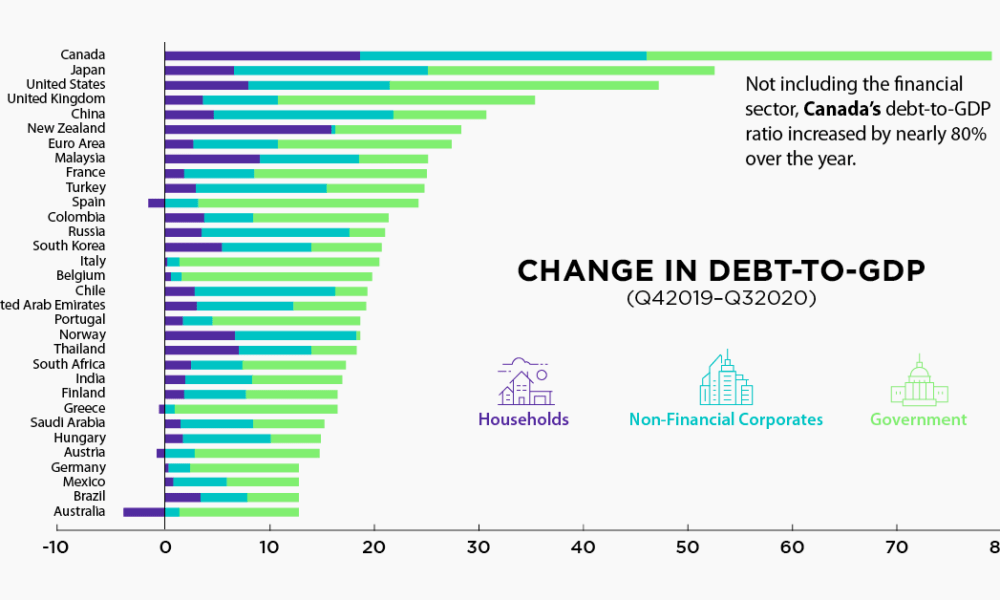

The beginning of the week was market by three, similar warnings, each of which add to the drumbeat of alarm over rising debt levels. In France the official government deficit was found to be higher than expected and contributing to a creaking burden of debt, then Larry Fink the head of one of the largest financial institutions warned of the ‘snowballing’ levels of debt accumulation, finally and perhaps most dramatically the Congressional Budget Office in the US has also been highlighting rising debt levels, and in a chart that will likely be repeatedly shared across the media, mapped forward the rising debt to GDP of the US government.

Rising debt is a pre-occupation of mine as many readers know (do listen to Waking up to World Debt). It will be impossible for the world economy to grow at a sustainably high rate until the mountain of debt that the large nations have accumulated is reduced. In recent notes I have started to cover how high debt levels will change politics, and on how indebtedness is part of the equation of great power rivalry.

Several other ‘truths’ are becoming clear.

Nearly fifteen years on from the global financial crisis, it seems that the policy community has largely forgotten the lessons of the crisis. I have re-examined three important books written during and in the aftermath of the crisis (Gary Gorton’s ‘Misunderstanding Financial Crises’, Raghuram Rajan’s ‘Faultlines’ and Mian & Sufi’s ‘House of Debt’), and in general the recommendations and lessons drawn out in those books remain ignored by the policy community. Debt has become an economic way of life. For reference, the UK public debt has gone from GBP 500bn before the financial crisis to GBP 2.6t trn today.

An remarkable facet of the rise of indebtedness is that it is correlated with other ‘crises’. For instance, there is a parallel between the growth of indebtedness and climate damage – average global temperature and indebtedness have grown in tandem (driven by the growth of infrastructure and industry in China in particular), and warnings of impending crises go unnoticed.

One reason for this is the adaptation of the economic system to both climate change and indebtedness, and the fact that policy makers are so far insulated from the consequences of each of these risks – the assumption is that central banks can now control bond market volatility, and so far catastrophic climate events happen ‘only’ in emerging countries.

While a scan of the long-run of economic history, and most finance textbooks would suggest that we should be in the antechamber of a debt crisis, this does not seem to be the case, and the adaptation of the economic system around debt is one reason for this. The prevailing assumption now is that the world economy can operate ‘normally’ in a climate of very high debt levels, and to coin a term we are in an ‘Age of Debt’.

The idea of the ‘Age of Debt’ is something that deserves greater attention, and as a framework it could have several characteristics. Here are a few.

One potentially dangerous trend is the rise of the ‘debt’ industry which is to say the emergence of a decent number of private credit firms in the US in particular, who can lend in a more liberal way than regulated banks.

A corresponding trend is the rise of fintech firms focused on lending (of the Top 100 most promising technology companies in the UK, according to Sifted, over a third are in the fintech sector and a good number of these involve digital lending). The ‘buy now/pay later’ service is a growing feature of many large fintech platforms. Many of these companies will use AI on scraped data and credit histories to decide which consumers are worthy of running up high personal debts.

The rise of the ‘debt industry’ is simply building debt distribution pipelines beyond the banks that have become heavily regulated as a result of the global financial crisis. To an extent they are doing what banks cannot do, and in some cases doing it better than the incumbent banks. To another, they are simply layering more risk onto the financial system.

An interesting element of this, is that the risks associated with rising debt are arguably becoming centred around individual countries. Up to 2007 the global financial system had become interconnected, which is why contagion spread across the international financial system. The global financial system led to enormous deleveraging and retrenchment of banks from overseas markets. This is reinforced by the growth of the ‘debt industry’ as lending focused fintechs and private credit providers are, to my calculations, operating within borders. The upshot of this is to make national financial systems riskier.

In time, the ability of national financial systems to work through debt will be a marker of the rise and fall of nations in the 21st century.

Have a great week ahead, Mike