A recent book, Samuel Moyn’s ‘Gerontocracy in America, highlights the growing concentration of wealth and power in the much older generations in the US, whilst younger generations face historically high valuations in real estate and financial assets, and how this growing intergenerational divide might be mended. Moyn, in my view, has struck a chord that will become one of the new dividing lines in politics, in Asia and the West.

His book brings demographic change into focus, a slow-creeping risk to economies, society and public life, but whose implications are only just surfacing in the public debate. Despite that, from a popular point of view, the sense in many Western countries is that there are too many people, or rather that infrastructure has not kept up pace with population growth – I am writing this in Dublin, which is an excellent case in point.

Yet, the long-run demographic trends – falling fertility, longer life expectancy and a shift in population composition towards a much smaller working (tax paying) population, will have enormous impacts on society, pension systems and debt loads, to name a few economic issues.

As much was evident in Germany’s recent pension reform debate which was nearly upended by Helmut Kohl’s grandson Johannes Volkmann and a group of other young parliamentarians who voiced the right of the younger generation to not have to shoulder the financial burden of their parents’ generation (under the German system, and many others, the working population effectively funds the retirement system of the older generation)..

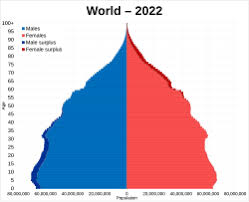

The best starting point on the outlook for demographics is the United Nations World Population Prospects website. and the data – especially in chart form – are quite striking.

The UN data show that as we approach 2100 the world population will plateau and start to shrink. From roughly 2080 onwards the world population growth rate will turn negative for the first time in centuries (wars apart), as the death rate passes out the birth rate. Within the age cohorts, the over 65 group will expand by a billion people in the next thirty years.

More specifically, at the country level, the US death rate will surpass the birth rate in around 2040, and population growth is likely to only be sustained by immigration. The picture is worse for some European countries – Italy for example is already in negative population growth territory, and the most negative forecast scenario from the UN has the Italian population dropping from over 60 million today to 25 million by 2100 (the same level as when Garibaldi unified the country).

Equally, China, which has been renowned for its economic and population growth, will endure a collapse in the 24–65-year age group, who today number 830 million people and by 2100 are expected to comprise 280 million people. China is projected to be the country most affected by ageing, with its, China’s elderly dependency ratio is projected to surpass 100% by 2080, meaning there will be more people aged over 65 than those aged 15 to 65.

The expected collapse in the working population begs serious questions for the economy – who will pay taxes, sustain pension systems and where will demand for financial assets come from. Markets are not worried, yet.

In general, researchers find that there is a positive link between demographics and asset prices, a finding that is predicated on the rise of the boomer middle class and the coincident equity bull market and fall in bond yields. The idea is that until they retire, working households invest more in real estate, equities and other riskier assets, but then shift to income-oriented assets like bonds as they get older and require income from investments. The oddity in that respect is that despite an ageing population, equities and real estate are very expensive. This may well owe to a growing investment culture, a record level of wealth (USD 500 trillion worldwide) and the prosperity boon that has resulted from globalization.

In this context, old money will become a political target, both in terms of demands for lower inheritance taxes, to more populist measures to tax the ‘old’ and give the ‘young’. For governments who worry about demand for their bonds, wealthier older citizens might make ideal candidates for financial repression (their children would face lower inheritance tax provided that capital spent a period of ‘purgatory’ invested in government bonds – I outlined a similar theme in ‘Patriotic Capital’)

At the same time, pension systems will have to change to accommodate a proportionately smaller number of workers (to pensioners). Private pension systems will become more common, they will invest more, earlier, with a tilt to riskier assets.

Concurrently, I expect to hear more on the need for states to establish sovereign wealth like funds (based potentially on the sale of state assets) to help provide for future pension liabilities. Another concern will be the need for states to cushion the potential blow of AI on workforces (a fund that holds equity in AI firms might be an avenue), at least through a transition period. In the long term, AI and robotics may well allow more older people to work for longer and for more women to enter the workforce. And, I haven’t managed to tackle the topic of later retirement ages and how that will impact the workforce and society.

The effects of demographics are not yet showing up in markets, and are just creeping into the investment industry, but it will become a major fiscal and financial megatrend.

Have a great week ahead, Mike