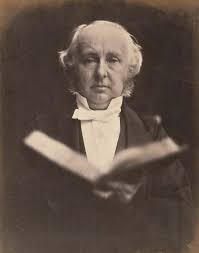

Benjamin Jowett is one of the prominent figures in the long history of Balliol College. Jowett, a scholar of Plato and university reformer, was Master of Balliol from 1870 to 1893, where one of his preoccupations was the production of upstanding young men who would then populate the civil service, and in particular who would be sent to ‘run’ India (Jowett favoured a thorough grounding in Greek and Latin as preparation for this task).

It is an understatement to say that India suffered under British rule, during the colonial era (roughly 1700 to 1947) which was marked by the activities of the East India Company, India’s share of world GDP fell from 26% to 4% (after the Second World War). It is still recovering today.

To draw the obvious comparison with Venezuela, which is apparently now to be run from Washington in imperial style (will Marco Rubio be referred to as the Praefectus of Venezuela?), it at least does not have to worry about having its economy destroyed, the revolutionary socialist governments of the past twenty-five years have done a good job of that. Rubio is not made in the mould of Jowett’s scholars, but he speaks Spanish, which will be useful. A knowledge of finance will also be handy, to tackle the mountain of debt that Venezuela owes.

In a week where the American president has been scurrying around like a giddy child opening Pandora’s boxes, the strategy for Venezuela is not yet clear, and it could go very badly wrong, especially if the factions within the current Venezuelan regime start to disagree violently.

The apparent upside is Venezuela’s oil reserves and refining capacity, but this will take a long time and much capital to realise. Indeed, the process of extracting and monetising oil, and driving this wealth into an economy is something that few economies have mastered.

In this regard, the idea of ‘Dutch disease’, a concept that initially referred to the effect of large gas finds on the Dutch economy, is well known, and colloquially, it describes the way the presence of natural resources can (negatively) skew the economic development of a country. Angola, which has been described as a ‘successful failed state’ for the way it has managed to extract and process oil, but does little else, is an example. Nigeria, Russia and of course Venezuela are other examples.

To their credit, the Gulf economies are good examples of states that have used the wealth generated by natural resources in a very ambitious way, whilst top of the league table are Canada, and Norway. Norway’s sovereign wealth fund is the benchmark for many others, and it bears imagining what the UK could have achieved by channelling the wealth from North Sea oil and gas reserves into a sovereign wealth fund from the 1980’s onwards.

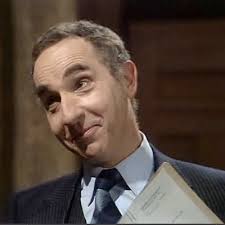

If there is a distinguishing factor across the relative success of the above nations it is the rule of law (and its associated values – policy clarity, strong institutions, and enlightened decision makers). The concept of the rule of law (I can recommend a book of that title by Tom Bingham, formerly Lord Chief Justice and Master of the Rolls and like Jowett a Balliol alumni) should be clear to most readers, but its benefits are even more apparent when it is taken away. In this regard, a comment from a US oil company executive regarding investment in Venezuela (in the FT) to the effect that “No one wants to go in there when a random f…g tweet can change the entire foreign policy of the country’ is illustrative of the benefits of the rule of law. Similarly, threats by President Trump to curb the dividend policy of defence companies, and institutional ownership of housing also contribute to policy uncertainty.

World institutions like the IMF and World Bank have produced tons of research demonstrating the link between the rule of law and growth, and stability. Yet the world that ushered in these institutions and globalization, is crumbling, vandalised by ‘world kings’ (Boris Johnson’s phrase) who act in an arbitrary way. Germany’s President Frank-Walter Steinmeier made an important speech to this effect last week.

The litmus test of this view will be the flow of capital. For the moment, the market view seems to be that ‘world kings’ get things done, and markets are reacting in kind. However, there are looming risks, notably the diverging values between the White House and Europe.

If world leaders were stupefied by the raid on Caracas, there was near hysteria in Europe at the suggestion by President Trump and his advisers that the US would annex Greenland. Though the initial reaction from politicians and commentators across Europe was perhaps overblown, there is a gulf between the American view of the White House’s foreign policy, and that of allies, and in the medium to long term this growing lack of alignment and trust will prove damaging.

Have a great week ahead, Mike