I’m glad to mention that my ‘GoldenEye’ note generated a lot of feedback, some of it cursing my good luck to spend a week in the Caribbean. To atone, I spent four days last week in the foggy cold of England, touring from Oxford to Manchester to the Cotswolds and finishing in London. Many of the places I visited are points of reference that I have known for a long time. Some have changed for the better (the Elizabeth line in London is very useful), some for the worse (this Manchester United team is indeed the worst ever), and some have not changed at all (the food at Pepper’s Burgers in Oxford is just as good as it was thirty years ago).

Economically and politically, Britain is worse off. Brexit has been a terrible mis-step, and the new Labour government is struggling to even diagnose the sputtering economy. Real-wage growth is feeble, productivity is at multi-decade lows, the fiscal deficit dominates policy making and the bond market is more troubled than when Liz Truss was prime minister. The only saving grace is that Britain isn’t Germany.

In foreign policy, while Britain is an active supporter of Ukraine and still a UN Security Council member, it is at risk of becoming lost geopolitically – Britain is stranded outside the EU and the special relationship between Washington and London is all but dead politically in the Trump 2.0 era.

However, Britain is good at remaking itself. I think that at some point it will have its ‘Brian’ moment when, to borrow from the Monty Python film (The Life of Brian), a political leader will emerge, haphazardly or by design, with the force of personality and ideas to right the country. Nigel Farage is not this person, and without being unkind, I am not sure that Keir Starmer is either.

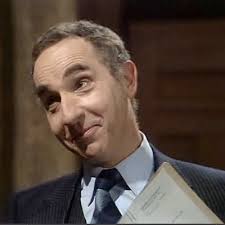

It used to be the case that Britain didn’t need talented politicians, it had a large, expert civil service to run the country. Instead of ‘Brian’s’ it had ‘Humphreys’ after ‘Sir Humphrey Appleby’ the fictional cabinet secretary in the excellent 1980’s tv series ‘Yes, (Prime) Minister’. The series revolves around the art of non-decisions and the careful practice by civil servants of keeping elected officials far from the levers of power.

When the engine of the economy was whirring, the job of the ‘Humphreys’ was to keep politicians from putting a spanner in the works. Now that productivity is dead across the UK (below the US, Germany and France) due to a lack of investment in capital and skills, the country needs to be inspired by new ideas. Thankfully, two of them came along last week.

The first was the latest in a series of notes on the UK economy by the excellent LongView Economics. In brief their diagnosis is that Britain faces several, long-growing problems – to many ‘Humphreys’ or rather too much regulation and bureaucracy (government spending is at seventy year highs), the death of risk capital and the need to re-generate investment flows across the British economy and the financialization of the economy.

Two of the solutions flagged by LongView are the needs to reform the NHS and to cut bureaucracy across government. This might happen sooner than many think because the second inspirational idea to come out of the UK was the launch a week ago of the UK AI Opportunities Action Plan, which in effect was authored by the venture capitalist Matt Clifford with a little help from the likes of Sir Demis Hassabis. It is applied and well thought through enough that it could not have been written by civil servants. In a week where the USD 500bn Softbank/OpenAI/Oracle AI investment has grabbed the headlines, the UK AI Plan deserves much closer attention and in my view, is the best framework for an AI value chain.

Whilst there are fifty recommendations in the report, all of which have been endorsed by the government, the main ones involve ‘feeding’ AI models by making high quality data more available (changing copyright laws), accelerate investment in data centres and also set up an AI Energy Council to plan the energy sources to power the data centres. There are also plans for a national data library and for the use of AI in the NHS.

One striking element, announced this Tuesday, is the use of AI assistants to speed up public services, with data-sharing deals across siloed departments; and a new set of AI tools — dubbed “Humphrey”. The aim is to speed up and make the work of civil servants more efficient – with the stated aim of saving GBP 55bn (this is very ambitious and if achieved would cut significantly into the budget deficit).

The plan, at least, is ambitious. Whether or not the Labour government can implement this plan is very much an open question but at least they have in their hands a blueprint for investment and perhaps the beginning of something better for the British economy.

Have a great week ahead,

Mike